American sports media hardly covers rhythmic gymnastics aside from some non-primetime space during the Olympics—during which commentators refer vaguely to “grace” and “beauty” far more often than they attempt to explain the rules. As a certified rhythmic gymnastics judge, I can assure you that these rules are complex. As a coach, I can tell you that most of my job is about teaching technique. And as someone who’s dedicated much of my life to rhythmic gymnastics, from my 14 years as an athlete to my current involvement, I think that the sport gets more interesting the better you understand it.

The thing is, the rules that govern rhythmic gymnastics encourage movements so fluid and aesthetic that, to the untrained eye, they appear mysteriously effortless. Top rhythmic gymnasts are so good at making their skills look easy that they almost convince spectators they really are.

Outside of its fleeting moment in the spotlight once every four years, rhythmic gymnastics has been described as “a pimple on the face of women’s sports” (by Lizzie McGuire) and “more like modern dance-meets-small-town circus than a traditional Olympic competition” (by New York Times writer Mary Pilon). When we’re lucky, we’re “cooler than you think” (thanks, Buzzfeed). In countries like Russia where rhythmic gymnastics is very popular, it’s viewed with admiration. But the limited American popular media portrayals of rhythmic gymnastics that exist often either claim it can’t be a “real sport,” or they marvel at its beauty without trying to understand its rules or describe its technical difficulty.

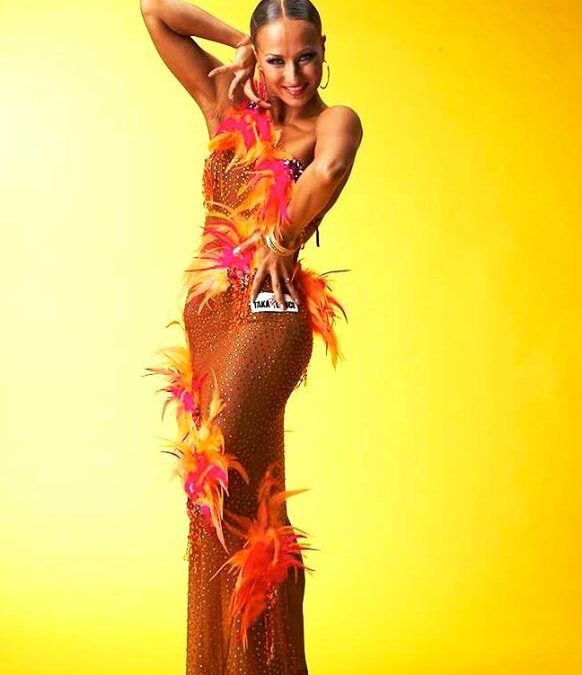

I’ve been thinking about how the American public views rhythmic gymnastics for years. As a child, I clumsily tried to defend rhythmic gymnastics against ridicule, and early on, I sensed that part of the problem had to do with the way we looked. I remember telling my parents that people might take rhythmic gymnasts more seriously if we all competed in identical, plain uniforms rather than sparkly leotards. Yet the problem extended beyond our outfits; viewers didn’t understand our ribbons, either.

A ribbon is to a rhythmic gymnast what a football is to a football player: a piece of athletic equipment. But jokes about rhythmic gymnastics often center around the ribbon, which has become the sport’s most recognizable apparatus. (Rhythmic gymnasts must also compete with hoop, ball, and clubs.) Ribbons have been likened to pieces of toilet paper on Twitter and in comedy sketches. People frequently and incorrectly call rhythmic gymnastics “ribbon dancing,” a name that does not position the activity as a sport. Ribbons look decorative. They look weightless. They are associated with hair accessories and frilly dresses—aesthetic, rather than athletic items. In short, are they too girly for the American sports world?

I hope not. Figure skating, after all, enjoys great popularity in the United States. More of the population understands, however, how difficult skating is. During the winter Olympics, journalists write with awe about skaters who successfully complete a quad. Books and movies describe top figure skaters’ lives, explaining the many hours of training that go into developing the fitness and technique required to move gracefully during competition. Especially in a sport with an aesthetic component, this type of knowledge makes a difference. Audience members who look for signs of effort on an athlete’s face may be confused by the way figure skaters or rhythmic gymnasts must in fact try hard to create an appearance of ease.

Even in artistic gymnastics (the formal name of the sport many know simply as “gymnastics”), athletes are allowed more signs of effort in their routines than in rhythmic gymnastics. Artistic gymnasts’ facial expressions typically remain serious and focused during all but the women’s floor exercise, and even then, athletes lose their smiles during tumbling passes. This is not to say that Simone Biles is doing it wrong; she’s simply doing a different sport. Under the rules of rhythmic gymnastics, an athlete should neither pause nor forget about aesthetic touches when executing her most difficult skills—and that means audience members need to know what to look for, lest they miss the tricky things entirely.

It’s time to treat rhythmic gymnastics as a legitimate sport. Let’s find knowledgeable commentators. Let’s write about it in sports publications. But to pull this off, we’ll need a change of perspective.

The difficulty in accepting rhythmic gymnastics as a legitimate sport goes deeper than what athletes look like and into the nature of what they are doing. Beauty itself is held as a feminine attribute, and a need to perform grace and ease is written into rhythmic gymnastics’ rules. Especially since athleticism has historically been considered masculine, the aesthetic and the athletic elements of rhythmic gymnastics may appear to contradict each other.

Rhythmic gymnastics’ struggle in the sports media landscape as well as its more general struggle to gain respect in the U.S. illustrates how the American perception of sports remains centered around men and masculinity. This perception works to the detriment of many athletes—rhythmic gymnasts, but also female athletes in general and athletes who do sports considered feminine.

In addition, I’ve been referring to rhythmic gymnasts as “she” for a reason: Olympic rhythmic gymnastics is a women-only event, and I believe that fact may contribute to America’s lack of understanding of the sport. Modern competitive sports, after all, began as a space dominated by men. The first modern Olympics in 1896 featured only male competitors, and although women’s gymnastics now receives more attention than men’s in the United States, it joined the Olympic program 40 years later. Given that most sports used to bar women from participating, rhythmic gymnastics is an outlier in that it bans men at the highest-level competitions. And as an all-women’s sport that highlights traditionally feminine qualities including beauty, it defies norms for what a “legitimate” sport looks like. (Artistic swimming, formerly known as synchronized swimming, is the one other women-only Olympic sport. It, too, often receives confusion or derision.)

I am open to the argument that rhythmic gymnasts should not feel pressured to conform to a particular image based on fashions within the sport. What I disagree with, however, is the suggestion that wearing leotards covered with Swarovski crystals or dancing to music as part of a routine somehow negates rhythmic gymnasts’ athleticism or technical expertise. I am also open—although this remains a point of controversy—to allowing male competitors. But I dislike the assumption that an activity could be less of a sport simply due to the fact that only girls and women do it.

0 Comments