Serchmaa Byamba is a professional contortionist and instructor. She was born in Mongolia, where the art of contortion originated. In 1992, Serchmaa rose to international stardom after she performed at the European Youth Festival. After moving to the US in 2012, Serchmaa turned her attention to teaching and raising the next generation of contortionists. This is her story.

Contortion is most commonly known as a circus art, with many contortionists displaying their extreme flexibility on shows like Cirque du Soleil and other performing arts troupes. What many do not know is that contortion has roots from Mongolia, where being a contortionist is a highly admired form of artistic expression. “Contortion is a very big art form in Mongolia. So many people think it is a circus art, which is how it is portrayed. But it is actually an art form that evolved from the national dance of Mongolia, and we have many years of history. In my home country, how it developed was from traditional dance movements. Eventually contortionists began to move further, and aimed to portray animal shapes with body. That is how contortion started.”

Serchmaa began her contortion training at age 7. She was inspired by her mother, who was also a contortionist. “My mom trained at Capital Circus in Mongolia with my teacher, but she didn’t pursue it professionally. She trained for three years, and when she graduated high school she chose to go to medical school. She never performed professionally, but when I was young, she would stretch at home and I grew up seeing her do contortion.”

When she was in first grade, Serchmaa attended a circus show, where she watched her idol contortionist, Enkhtsetseg Lodoi, perform. “My first grade teacher, my mom and some of my friends and I went up to her after the show, and we asked her if we had the talent for contortion, and if she could check our flexibility. She checked, and picked me out of all the girls. She gave me the name of a teacher: Madame Tsend-Ayush. ‘You can go to her in the Capital Circus, introduce yourself, and I will send you to her.’ That’s how I started.”

When Serchmaa began her training, Mongolia was socialist country, and aspiring contortionists were hand-picked by their teachers and trained at the Capital Circus, which was directed and funded by the government. “We were chosen by our teacher, and then worked under her direction. We trained for free, but after we graduated we worked for the circus, and everything we made would go to the circus.”

Like a professional athlete, Serchmaa adhered to a strict training schedule growing up. “I trained 3-4 hours a day, 6 days a week. We couldn’t miss classes. If you don’t show effort, then the next person is always waiting to take your spot, and you will get cut. It was very strict, but that’s how it should be when you are involved in professional training. I was very happy and honored to work with my teacher, Madame Tsend-Ayush, who was a legendary contortionist and performer, and having that many hours working with her was an amazing opportunity. She is a queen in the contortion world, and everyone knows her name.”

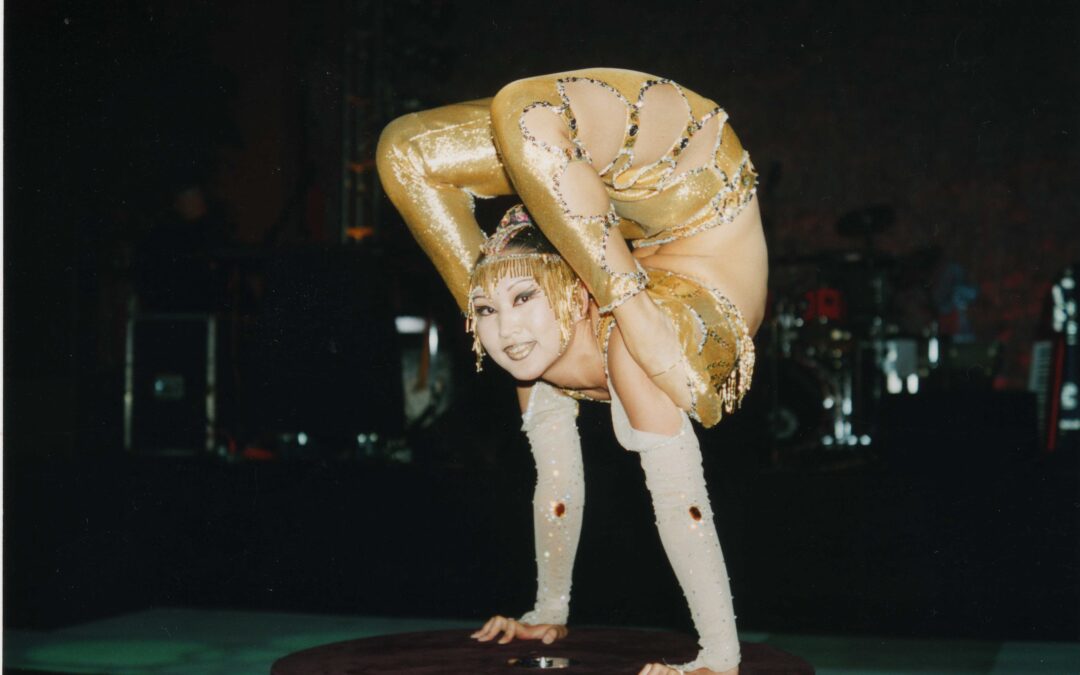

Serchmaa trained for four years before breaking into the performance scene. In 1992, Serchmaa was invited to perform at the European Youth Circus, where she gained international recognition after winning the Golden Elephant audience award. She subsequently earned the nickname, “Golden Girl”. To this day, she is the only Asian ever to be invited to participate in the European Youth Circus Festival. When asked about her rise to stardom, Serchmaa says, “I really live this art. It is my passion and I dedicated all of my life to it. Living my dream and passion, I think I just gave it everything I had! I wouldn’t say that I’m the ‘star’, but I really do have a big passion for this art.”

Just as she began working for the Capital Circus, the political landscape of Mongolia shifted from a socialist to capitalist country, and the entire system changed. “Circus performers started going different directions on their own and many no longer worked under the Capital Circus. I did the same thing. I was a new contortionist when I cut my contract and began performing for another circus, the National Ensemble in Mongolia, where I worked for a year. Then I came to San Francisco when I was 20 years old and started working at Circus Center, where I became a teacher.”

When asked about the typical career trajectory of a professional contortionist, Serchmaa says, “Our career path is very simple. When you’re ready to perform you live on the stage in front of people. Contortion is like any other art form– we use our body at the extreme level– and there is a limited time you can do it and be able to challenge your body mentally and physically. You dedicate so much time to being on the stage, and your life revolves around the art. Contortion is the same as any other art genre– we have only a certain time available, and after that you ask, what’s next? Some people choose to teach, like me, because I just couldn’t stay away from the art. Some people change their path to directing and choreographing shows.”

While contortion is immensely demanding on the body, the retirement age of contortionists is wide-ranging. “Because Mongolian contortion technique is so precise, many contortionists from Mongolia can do it for many years. For example, 7 years ago I went to Mongolia to perform with my idol contortionist, who was 60 years old at the time. When you stop depends on how much you are holding on to it, and how much work you put into it, which determines how long you can keep going.”

Serchmaa stopped performing professionally at age 35. When asked why she chose to retire, Serchmaa explains, “I stopped early, but it was my personal choice. It wasn’t because I couldn’t handle it, but I just wanted to stop and dedicate my time to my family. Being a performer you’re always traveling and on the move, and you aren’t able to build your own life. You see your kid is growing before your eyes and you aren’t able to spend time with them. This is the sacrifice many artists make. I completely stopped so I could take my heart away from performing and stay focused at home, so I could spend more time with my family. I also wanted to dedicate more of my time to my students. Without commitment from both teacher and student, it is hard for students to learn. [Retiring early] worked for me, and I have no regrets.”

Upon retiring, Serchmaa immediately turned to teaching contortion at the Circus Center in San Francisco, California. Growing up in Mongolia, where most aspiring contortionists start their training in childhood, Serchmaa was surprised when an adult student showed up to her class. “The first class I taught, I expected kids. Then I had an 18 year-old girl enter my class, and I was very confused. I went downstairs and said, ‘I think this girl entered the wrong class,’ and I was told that my class would be for both professional and non-professional contortionists, and there were people with no contortion background who would take my class. So I went back into the room and told this girl, ‘Just show me your flexibility.’ And I was amazed! I was totally excited to work with her.”

Serchmaa’s experience training adult contortionists dispelled the notion that it is impossible for late starters to pursue contortion professionally. She has many students who started contortion in adulthood, and have gone on to lead successful performing arts careers, performing in many local and international shows and circuses. “It is not impossible to start late and become a professional contortionist. But based on your body type things can be different. This is why I like to work with my students individually. If I can understand each individual body type, I can work with it. As a teacher, you have to connect with your students’ body type, and based on that you can challenge how much they can do.”

A firm believer in the power of hard work, Serchmaa says, “There is always possibility if you work hard. Talent is 1%, and 99% is work, for everything. I really truly believe that. Some teachers say to their students, ‘You will never be able to do [contortion] because you will never get flexible.’ I am really against this. You just cannot kill someone’s passion like that. Of course I will not promise everyone that they can be a professional contortionist. But I tell them to do it as much as they can challenge themselves. Everyone has their own type of flexibility and body, and from that they create their own unique style and movement. Based on this technique, you can become a contortionist. No one contortionist will look the same. That’s so beautiful to me, and that makes me so proud and fulfilled as a teacher.”

Serchmaa enjoys the challenge of working with adult students, in particular. “Kids, I can move them however I want to. Their bodies move before their brains. But adults, you have to understand them, otherwise it doesn’t work. When they start doing their splits and handstands right in front of my eyes, you know how they started, and you see how perfectly they’re doing it now. It’s so beautiful. That’s why I really like working with adults. It’s very hard, but very rewarding.”

Presently, Serchmaa teaches online contortion classes for both kids and adults. She is in the process of creating her own online contortion curriculum, set for release in 2022. The program is catered to people of all ages and experience levels. “My program is built for people who are starting from scratch. Because Mongolian contortion technique is so polished, anybody can benefit from it. Our program emphasizes total body training. We train flexibility from neck to toes. But we emphasize strength as well as flexibility, because you need to have strength to support the flexibility. Mentally, contortion teaches you discipline. You must learn to calm your mind onstage when you are doing a handstand. This mental discipline starts from your physical training.”

When Madame Tsend-Ayush passed away, Serchmaa resolved to pass on her teacher’s lessons to the next generation of contortionists. In 2012, Serchmaa founded her own contortion center in San Francisco, called Mongolian Contortion Center. “My teacher’s last words were, ‘Carry my name high, and carry this art beautifully.’ I didn’t have a chance to see her when she passed away, but I try to live out her words. I try my best to pass on Mongolian contortion, as the technique is all built from my teacher’s. It is the least I can do to honor her. I have had lots of disagreements with people who want to do work with me and want to change the name of the contortion center, because the name ‘Mongolian Contortion’ scares people. Sometimes a business offer will come with a promise to make a lot of money and be successful. But I wouldn’t change the name and direction of my center. For me, success isn’t about money. I never want to take away the Mongolian Contortion name. I would rather keep this art going with the same name and same direction, rather than reaching thousands of people but losing what it is.”