Historically called synchronized swimming, the sport was renamed in 2017 to artistic swimming in an effort to clarify the nature of the sport. In this article, per agreement with the interviewee, we will use the terms artistic and synchronized swimming interchangeably.

Kate Molenaar is a 22 year-old synchronized swimmer who has competed on the club and collegiate levels for 12 years. In 2015, she and her team, the Northern Colorado Orcas, won second place at the Junior Olympics. Kate began college at Colorado State University in 2018, where she was a member of CSU’s synchro team for all 4 years. A recent college graduate, Kate prepares for her next dive: physician assistant school. While no longer pursuing synchro competitively, Kate still enjoys swimming for personal enjoyment. In this feature article, Kate shares the highlights of her synchro career, challenges and psychological pressures faced along the way, and lessons gleaned from her life spent underwater.

Kate was first drawn to water sports at age 10. While at her neighborhood pool one day, she searched for open diving boards to jump on. The diving boards were closed, however, as there was a synchronized swimming demonstration going on. “It was a ‘try-it-night’ kind of thing. I couldn’t dive, so I gave [synchro] a try. I was, like, not excited about it. But I actually really liked it during that hour! I’d never been a really athletic person, ball sports and P.E. were not my thing, so I thought I was just not interested in sports. But I gave this a try.”

Kate’s parents then signed her up for the Northern Colorado Synchro’s summer team. “The summer team is a much more relaxed, less competitive side of the sport. So I just tried that and I really liked it. I was on a summer team for four years, and then I transitioned to age group when I was 14.”

Synchro Levels and Categories

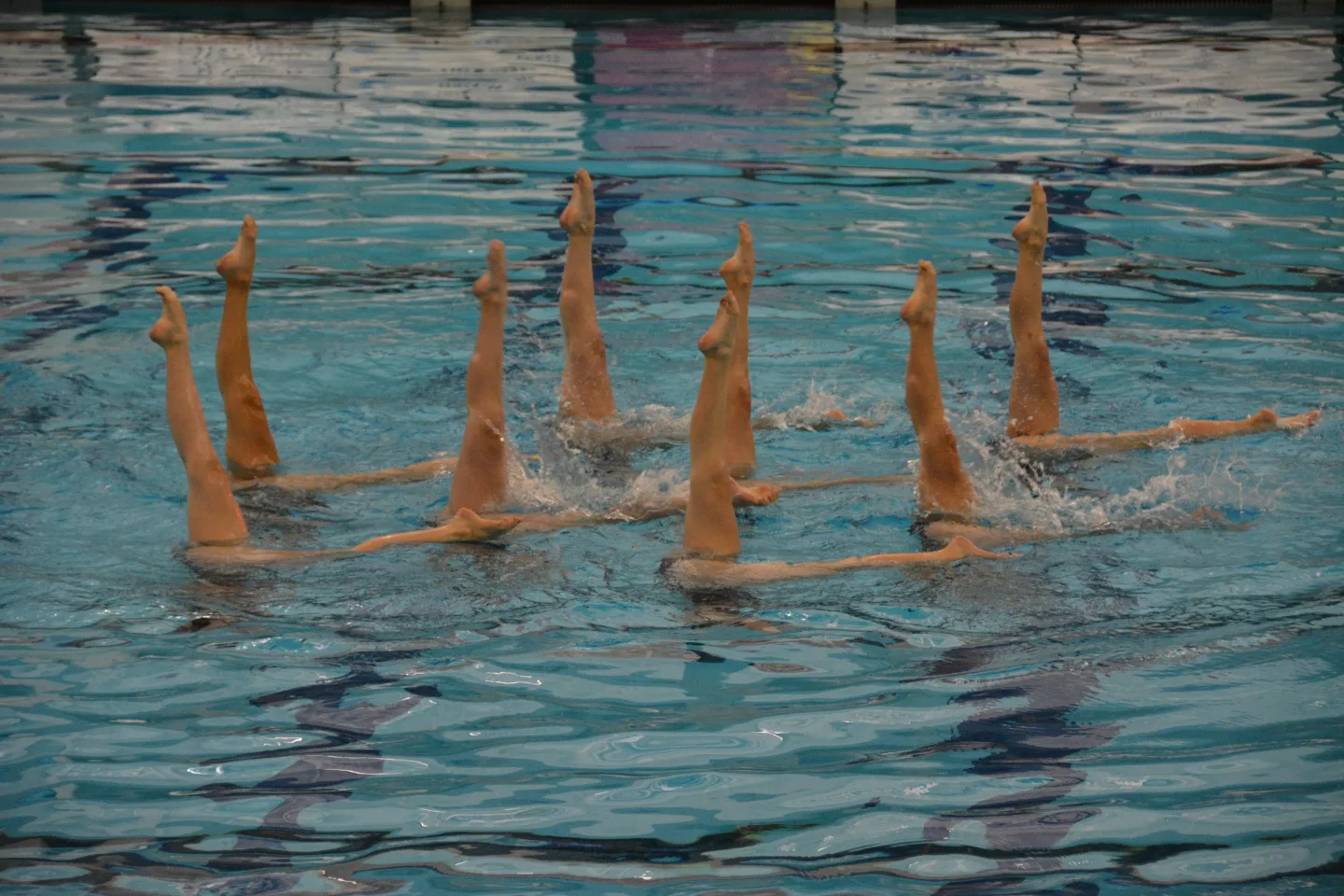

USA Synchro is divided into three levels: novice, intermediate, and age group. Of the levels, age groups teams are the most competitive division. There are various categories synchronized swimmers compete in. Team routines range from 4-8 swimmers. Combination routines are larger, comprised of 10 swimmers. There are also trios, duets, and solo events.

“I’ve done all of [the events]. I like teams best partially because that’s what we traditionally devote the most energy and focus to. Team routines are where you see someone being thrown out of the water. I’m pretty light, so I was usually a flyer, which is very fun.”

Training

At age 14, Kate moved into age group level synchro, which demanded four times a week of training with 11 hours per week during the school year, and 24.5 hours per week during the summer.

A typical practice was as follows: half an hour of landwork, mostly calisthenics and stretching, maybe 30 minutes to an hour of laps, including some things that regular swim teams normally wouldn’t do. They would then devote 1-2 hours to work on competition routines.

“We would do things called ‘unders’. This is the way we train to [hold our breath so long]. You swim the entire length of the pool without coming up for air. It’s difficult on its own for someone who hasn’t done it before, but then we would also combine it with pretty intense swimming and other grueling sets, and we would have it [performed] on time. The longest I’ve been under water is 2 minutes.”

Kate recalls one particular coach who pushed their swimmers to the brink of consciousness. “My vision would go gray. I would not be able to see color from oxygen deprivation and she would just make us go again. So that is how people pass out. I have never passed out myself, but I know some other girls who have. No one I know has ever died from it because we’re all pretty capable swimmers. But one person I know passed out doing an under, and her teammate had to save her.”

Looking back on the sheer intensity of competitive synchro training, Kate says, “It’s definitely kind of crazy, thinking back, that I pushed myself that hard, to the point where I couldn’t see color and was seeing stars, and then I would just keep going. But we all did that. It was just kind of expected.”

Competitive Highlights

“Probably my biggest claim to fame in synchro is when I was 15. [My team and I] got second place at the Junior Olympics and got Silver medals and everything. It was kind of a breakthrough moment for our club. The Orcas have never been super competitive until my generation of swimmers came along. The year before, our team went to the Junior Olympics and they placed 14th. They had been trying to get into the [top 12] finals that whole season, and they didn’t quite make it. Our goal for the first season I was on the team was just to get into the finals. We got second, and that was way better than we thought we would have done.”

Senior Nationals 2016

“My second favorite memory was the next year after that, at Senior Nationals. That was just really fun from a competitive perspective, of course. But also our team rented an Airbnb and it was the most beautiful house in Arizona that had a pool in the backyard, and it was just a really fun time hanging out with the team.”

Hiatus from Competition

During her senior year of high school, Kate took a one year hiatus from synchronized swimming. “My senior year of high school was the one year since I was ten that I didn’t swim. I was planning to, and then the few people that were still my age either couldn’t afford to swim or decided to move to different team that was in Denver, but I wasn’t able to commute to Denver. I was really sad and torn over it. So I did not swim that year. I was really happy to get back into it in college, though.”

Mental Health and Synchro

Eating Disorders

“I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about eating disorders in the context of Synchro. I think that’s probably really common in any aesthetic sport because you’re literally being judged on your body and how your body moves. The judges are watching the way that you move your body and how subjectively beautiful they think that is. There’s a lot of pressure from coaches and other swimmers just to be as thin as possible. The traditional synchro body will have long, thin legs, and swimmers will generally be tall. But more importantly is being thin. Traditionally that looks the best in the water. There are very few larger women that make it to Collegiate Synchro. Even if you watch finals at the Junior Olympics or even in smaller meets, the girls who do well are thin, whether that’s because thin people are generally more athletic, or if it’s that the judges have a bias towards thin people, which I strongly believe there is, whatever the reasoning for it. And that contributes to a lot of issues, for sure.”

“On my team of 8 people, at least 6 had some level of disordered eating. And for most of [them], it was really bad.”

“Most of the fatphobia was unspoken and more reinforced by who you saw on the podium and who you saw getting solos. Solos are pretty coveted because it’s traditionally the best people on the team who will get them. There are also things our coaches would say. I remember, to one duet, one of our coaches said, “I want you to look like those two.” And that wasn’t said directly to me, but it was related to me. I heard about it and I was like, “Well, she didn’t say my name, even though I have a pretty traditionally Synchro-esque body. So I’m not enough. I should try to look more like them.’ Which doesn’t work. You can try, and you can ruin yourself over it.”

Asked whether USA Synchro has pushed for greater body inclusivity in recent years, Kate says, “A few years ago, there was a pretty inflammatory New York Times article that came out, mostly about national team girls, that reported on the absolutely horrible things that had been said to them about losing weight. They’re already the most elite athletes in the country, like, come on. I don’t know if USA Synchro has taken any official steps to combat that. I know that when I was a coach, briefly, I had to do something called Safe Sport. It’s training on how to not hurt your athletes mentally. I’m not sure if that was implemented for my coaches when I was swimming before college.”

Perfectionism

Aesthetic sports like gymnastics, figure skating, and synchronized swimming demand from their athletes meticulous precision in execution of difficult skills, with the added expectation of making such skills appear effortless in a choreographed routine. The high demands of these sports can foster perfectionistic concerns in athletes, defined as: concerns about making mistakes, feelings of discrepancy between one’s standards and performance, and fears of negative evaluation and rejection by others if one fails to be perfect.

Kate discusses her issues with perfectionism as a byproduct of her experiences in synchro, and how such perfectionistic concerns bled into her life outside of sport. “The perfectionism comes from being told that there isn’t a point where you can rest and where you’ve done enough. That’s why, in school, I feel like I have to get a 4.0 GPA all the time. I am definitely still a perfectionist, like all through high school and college. I got straight A’s which I’m proud of myself for. That was a ridiculous amount of work, and just the amount of pressure I was under… I was literally afraid of getting a B at one point. I don’t know what I would have done with my mental space if I had gotten a B, like truly. I don’t. The perfectionism, probably in any aesthetic sport, is overwhelming and can just drown [you]. I think that’s why, at least for Synchro, a lot of people don’t make it past age thirteen to fifteen. This is the largest age group in Synchro. Once you get to age group competitions, thirteen-fifteen is the biggest. People just start dropping like flies after that. And I think it’s because of the amount of pressure you’re put under. It’s just hard to balance that with everything else that’s going on during that age. You’re going through body changes like puberty, and then having to deal with the eating stuff, and the rising caliber and competitiveness of the sport on top of school.”

Performance Anxiety

Asked whether she experienced performance anxiety, Kate says, “I think that most of my anxiety was centered around practices more. That coach I told you about, who would make us keep going when our vision was going gray… so those practices with her were on Tuesdays. I would start getting physical chills in my body on Sunday. Like, dreading Tuesday.”

“I did get performance anxiety, though. I remember my first big swim at the Junior Olympics. I had been in Junior Olympics the year before but not done very well because that was my first year in age group. So before the final swim, I was incredibly nervous. I got 2 hours of sleep. I was just laying there, trying to sleep that whole time, but I kept playing through my mind this really critical moment in the routine, a really difficult lift. People would be egg-beating and hold their hands up and lock their arms, and basically form a ring, and then I would come up and do a push-up into the middle of that circle to get myself onto their hands. Then I plant my foot on the back person’s arm and do a standing split like a needle. There were just so many things that could go wrong. And so, I over-thought that a lot. Right before we went on, I actually threw up on myself literally moments before walking out on the stage. I did fine, obviously. But it was a lot.”

Transition out of Competitive Synchro

“It was kind of hard, losing an identity during my senior year of high school. At that point, I’d been swimming for eight years and especially during high school, it was the most time-consuming thing I did outside of school, and then suddenly I kind of lost that identity. It was like losing that piece of yourself you consider to be the most unique and best thing about you. It’s part of why I’m still swimming. I still get to keep that identity, and I think even retired athletes should [get to keep it]. You’ve earned your stripes, you know what I mean?”

Presently, Kate has her eyes set for her next dive: physician assistant school. “So, I’m applying to physician assistant schools, which is kind of a fun tie back to Synchro, just because I became a lifeguard and because of lifeguarding, I learned basic first aid, and I was like, ‘This is really cool.’ I really, really enjoy this basic medical stuff, and I realized I wanted to be a provider.”

In terms of life after competitive sports, Kate says, “One of my favorite things about life [now] is finding out that I like to exercise in different ways! I’ve been really enjoying running, stand-up paddle boarding, hiking, and yoga, which I never had time or energy to fully explore when I was so busy with synchro.”

Asked what advice she would give to her thirteen year old self, Kate replies, “You can be your own person. Part of the beauty of an aesthetic sport is the creativity and the uniqueness of every routine, and that includes who you are and what your life looks like.”

In her free time these days, Kate is out at the pool, still swimming, but purely out of love and enjoyment for the sport that will forever remain a part of her.